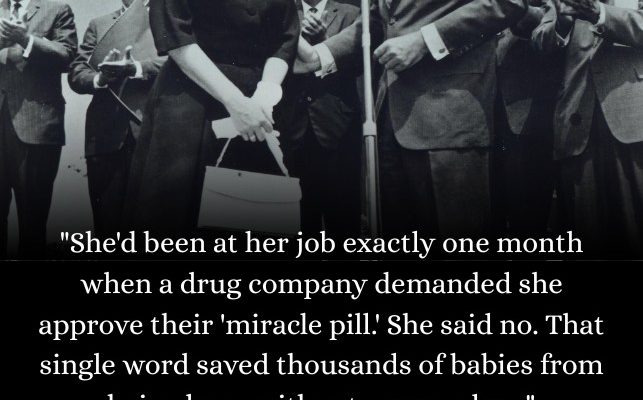

She’d been at her job exactly one month when a drug company demanded she approve their “miracle pill.” She said no. That single word saved thousands of babies from being born without arms or legs.

In August 1960, Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey walked into her new office at the FDA as one of only seven full-time physicians reviewing drugs for the entire nation. Her very first assignment seemed routine: approve thalidomide, a sedative already used safely by millions across Europe and Africa for morning sickness and sleep troubles.

The pharmaceutical company Richardson-Merrell had already stocked warehouses with ten million tablets. They expected approval before Christmas. They were planning to make a fortune.

But when Kelsey opened the file, something felt wrong.

The safety data had gaps. Animal studies were weak. Human trials were incomplete. The company’s “evidence” looked more like marketing materials than science. And buried in European medical journals were troubling reports of nerve damage in long-term users.

She had questions. She asked for more data.

The company exploded.

For eighteen months, Richardson-Merrell executives waged war on this one junior medical officer who dared to slow their profit machine. Sales reps crowded her office. Phone calls came day and night. Corporate officials contacted her and her supervisors approximately fifty separate times, demanding she stop stalling and approve their drug.

They called her names she later said “you wouldn’t print.”

The pressure was crushing. The drug was “perfectly safe”—after all, millions of Europeans used it without problems. Company executives insisted she was holding up a wonder drug over meaningless technicalities. They tried going over her head. They threatened. They bullied.

But Kelsey remembered something from her early research days at the University of Chicago. She’d studied how pregnant rabbits metabolized drugs differently than adults—and how certain medications crossed the placental barrier to affect developing embryos.

When she looked at thalidomide’s “safety” claims for pregnant women, she asked one critical question: Had anyone actually tested what happens when this drug crosses into a developing fetus?

The answer was no. Nobody had.

So every sixty days, when FDA regulations required her to either approve or request more information, she requested more information. Every sixty days, she found the new data inadequate. Every sixty days, she refused to sign.

Her supervisors stood by her. She held her ground.

And then, in late 1961, the nightmare began appearing in European hospitals.

Babies born with arms and legs grotesquely shortened or missing entirely. Hands sprouting directly from shoulders like flippers. Hearts, eyes, and ears severely malformed. Internal organs improperly developed. The deformities were shocking, catastrophic, heartbreaking.

At first, doctors couldn’t understand why. The cases seemed random, scattered across different countries. Then the pattern became unmistakable: every mother had taken thalidomide between the twentieth and thirty-sixth day of pregnancy—the exact window when limbs and organs form.

The drug companies had marketed as “perfectly safe” was causing catastrophic birth defects.

More than ten thousand children across forty-six countries were affected. About half died shortly after birth. Thousands more pregnancies ended in miscarriage or stillbirth. The survivors faced lifetimes of profound disability.

Germany pulled the drug in November 1961. Britain followed in December. Other countries scrambled to respond. But the damage was done. An entire generation of children had been harmed.

In the United States, something remarkable happened: almost nothing.

Because Frances Kelsey had refused to approve thalidomide for general sale, it never reached American pharmacy shelves. Richardson-Merrell had illegally distributed experimental samples to about twelve hundred physicians—resulting in seventeen confirmed U.S. cases and dozens more suspected.

Seventeen American children harmed—a tragedy, but not the catastrophe that devastated Europe.

Thousands of European children harmed—because their regulators approved the drug without adequate testing.

The difference was one woman’s refusal to accept insufficient evidence.

When Americans learned what had been avoided, the reaction was explosive. A Washington Post reporter wrote a front-page story calling Kelsey a heroine who had prevented “the birth of hundreds or indeed thousands of armless and legless children.” Public gratitude was overwhelming. Public fury at the drug company was intense.

On August 7, 1962, President John F. Kennedy presented Frances Kelsey with the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service—the highest honor for a civilian federal employee. She was only the second woman ever to receive it.

But the real change came next.

In October 1962, Congress unanimously passed the Kefauver-Harris Amendment, fundamentally transforming American drug regulation. For the first time, pharmaceutical companies had to prove drugs not only were safe but actually worked. They had to report adverse reactions. They had to obtain informed consent for clinical trials. Testing standards became rigorous. Protections for vulnerable populations became law.

Frances Kelsey helped write those regulations. She led the FDA division responsible for implementing the reforms. Her team earned the nickname “Kelsey’s cops” for their uncompromising oversight. She spent forty-five years making sure that what almost happened with thalidomide could never happen again.

She retired in 2005 at age ninety. She died peacefully on August 7, 2015—exactly fifty-three years after receiving that medal from President Kennedy. She was 101 years old.

Frances Oldham Kelsey never made a groundbreaking discovery. She never invented a lifesaving device. She never developed a cure.

What she did was refuse to compromise. She asked questions when everyone wanted quick approval. She demanded proof when proof didn’t exist. She withstood crushing pressure from powerful corporations and held firm to her scientific standards.

She proved that courage isn’t always about bold action. Sometimes courage is the quiet insistence on doing things right. Sometimes it’s the refusal to bend under pressure. Sometimes it’s the willingness to say no and mean it, even when the entire world is screaming yes.

Her decision saved thousands of American families from devastating heartbreak. Her example reshaped medicine worldwide. Her legacy protects every person who takes prescription medication today.

All because one doctor understood that the most powerful word in medicine isn’t always yes.

Sometimes, it’s no.